Yesterday, we grabbed our SRFboards and hit the beach to discuss how we Support or Refute statements about the world with Facts (if you missed out, feel free to dip your toe back in the water by reading Everybody’s Gone SRFing). Whether you choose to SRF with anecdotal or empirical evidence, it’s important to share the techniques you used to gather your data. Good SRFers use multiple techniques to gather data and answer a research question. Sometimes, this is referred to as triangulation1. Think you’ve got what it takes to ride the waves? Then, paddle out and join me in the surf. Let’s talk about variables!

What is a Variable?

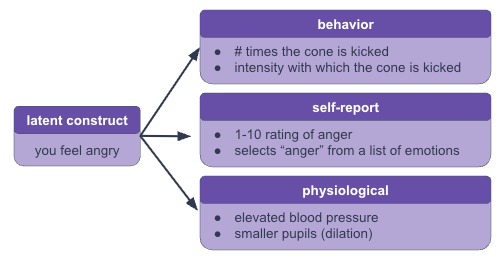

As a human researcher2, I focus on collecting evidence of the thoughts, feelings, attitudes, and beliefs that people hold. Human researchers refer to these things as latent constructs. For example, anger3 is a latent construct. Something happens (a stimulus), you feel angry (the latent construct), and this anger motivates you to act in some way (a response)4. Since I can’t directly measure a latent construct, I need to infer it through your response to a stimulus. The response(s) that I choose to record are called variables.

When researchers use variables to SRF, they share 3 key pieces of information:

What they measured,

How they measured it, and

When they measured it.

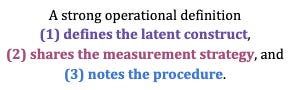

In research, we refer to these things as (1) defining the latent construct, (2) sharing the measurement strategy, and (3) noting the procedure. Since we have already selected a latent construct (anger), we’ll start by talking about measurement strategies.

Sharing the Measurement Strategy

As you know, there are many different responses that a person could have to anger. Consequently, there are many ways that we could measure anger (see Figure 2).

For example, we could measure anger using self-report, behavioral, or physiological measures.

A self-report measure captures a latent construct by directly asking a person about it (e.g., “How angry are you on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (a lot)?”).

A behavioral measure captures a latent construct by inferring it from a person’s behavior (e.g., a person who punches a wall must be angry).

A physiological measure captures a psychological construct by inferring it from changes in a person’s moment-to-moment physical symptoms (e.g., a person’s heart rate and blood pressure increase when they get angry).

If you want more examples of measurement approaches and considerations, check out my other post, Giving The Spherical Cow Some Night Vision Goggles.

Noting the Procedure

Once we decide which measure to use to capture a latent construct, we must decide when we want to measure it. Researchers have many established methods by which to do this; if you took a research methods class, you’d learn about them! For today, let’s use just a few approaches to illustrate the diversity of procedures you might find while SRFing.

The One-Group Design

One way we could assess our latent construct is with a one-group design: expose people to a stimulus and measure their response. For example, we could expose a single group of people to an upsetting situation (stimulus) and then measure their anger immediately afterward (response/variable).

The Two-Group Design

Another way we could assess our latent construct is with a two-group design: expose two different groups of people to two different stimuli and measure their responses. For example, we could expose 50% of the people in our research study to one upsetting situation (stimulus) and then measure their anger immediately afterward (response/variable). The other 50% of the people in our research study could be exposed to a second upsetting situation (stimulus), and their anger would be measured immediately afterward (response/variable).

The Repeated-Measures Assessment

A third way we could assess our latent construct is with a repeated-measures design: expose one group of people to two different stimuli and measure their responses. For example, we could expose 50% of the people in our research study to one upsetting situation (stimulus), measure their anger (response/variable), then expose them to a second upsetting situation (stimulus), and measure their anger (response/variable). The other 50% of people would experience the same thing, but with the upsetting situations reversed.

Sharing How We Measured

Since there are many ways to systematically gather evidence, it’s important to share exactly how we did it. Researchers call this operationally defining their variables. A strong operational definition (1) defines the latent construct, (2) shares the measurement strategy, and (3) notes the procedure.

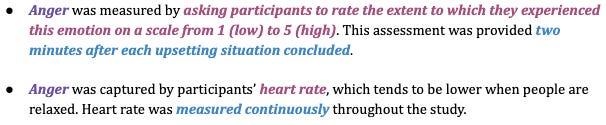

Here are some examples of how we might operationally define the variables we discussed in this article:

This term is used differently in counseling psychology, where it refers to bringing an unwilling third party into a conflict.

I use this general term because humans are studied by people in many professions: psychology, human factors, kinesiology, medicine, engineering, and software development, to name a few.

If you want to learn more about emotions, like anger, I highly recommend Paul Ekman’s Atlas of Emotions website. The Atlas of Emotions illustrates the leading theory on how emotions form, discusses the nuances of different emotions, and provides thought-provoking information about what different emotions feel like and how they can be managed.

This basic framework is the backbone of stimulus-response theory, one of several explanations for complex behaviors, like learning (Holland, 2008).